|

Published in the Viewpoints section of the Chicago Maroon, the student-run newspaper of the University of Chicago.

We activists can seem impossible to please: We seek a goal—say, a U of C trauma center—and, after years of struggle, the institution gives in. But then we continue to advocate—say, for a U of C Medicine community advisory board—and the process begins again. When will we be satisfied? But of course, social justice is at once a process and a goal. With the U of C, we’ve achieved a goal—a trauma center—and faster than even many of us in the Trauma Care Coalition foresaw one year ago. But we’re still watching and working on a process. And lately, what we’ve seen has not been promising. To state the obvious: to remedy injustices like unequal healthcare, we would rather not have to protest. We would rather not have to push for meetings and plan teach-ins and pray on a street corner week after week for years. Yes, doing all that has built incredible leadership and allyship among our communities. But we have yet to see what the U of C has learned from it. Has it learned to value young Black lives? Not only with promises responding to pressure, but with processes to shape its priorities going forward? That’s why, since January, our Coalition has focused on the U of C Medicine’s talk of a community advisory board. The U of C might institute a board with little diversity, little access to decision-makers, and little power. Many South Siders at our recent town hall meeting explicitly feared as much. But if the U of C institutes a board that seats all of our Coalition member organizations, meets regularly with executives and trustees, and addresses concrete decisions, it can work. And we can work with it. Unfortunately, even that seems to be in question now. University and Medicine vice presidents told Coalition leaders weeks ago that information about a community advisory board’s composition would be announced at their Urban Health Initiative summit, last Tuesday, May 24. The U of C invited the Coalition to the summit, and we sent several of our leaders. An executive director in U of C Medicine confirmed the announcement with Coalition leaders at the event, saying that it would happen at its close. But no announcement was made. In asking for such a board, are we activists asking for too much? Not if we seek a long-term process by which the U of C Medicine can register with its neighbors’ many other challenges, like chronic illness. Not if we seek partnership over protest. But if the U of C will not even advance such a process—then, inevitably, these struggles will go on. Published in the Viewpoints section of the Chicago Maroon, the student-run newspaper of the University of Chicago. Photo: Wei Yi Ow.

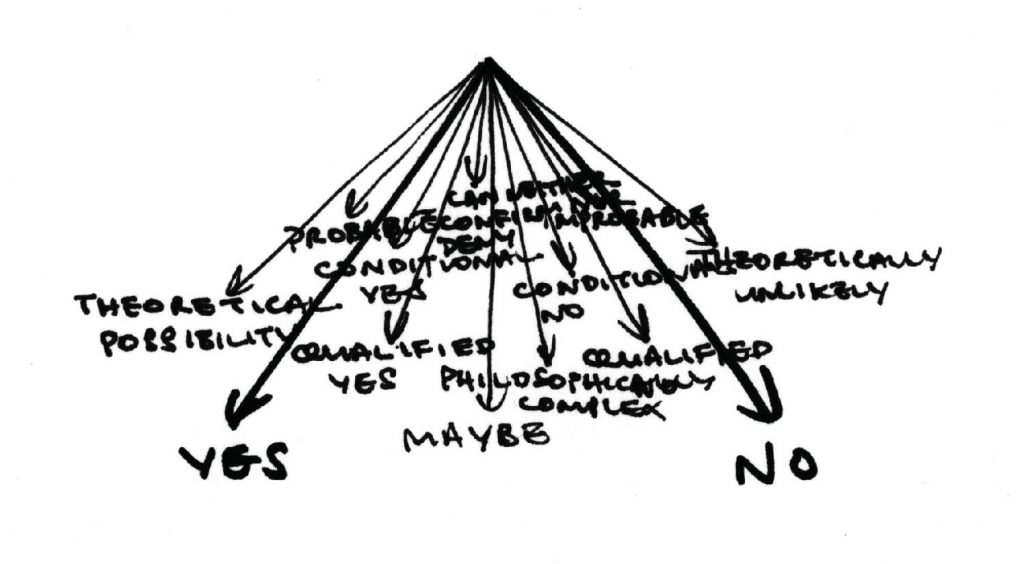

On Monday, May 24, at Student Government’s last assembly of the year, outgoing provost Eric Isaacs invoked academic ideals to resist multiple questions about his decisions: “We’re the University of Chicago; we’re really about discussion and debate—we’re not about yes or no questions,” Isaacs said. This would be all well and good were we students in a classroom or faculty at a conference. But Isaacs was addressing his Title IX staffing, minimum wages, meetings, and more—and not in an academic setting. This recalled Daniel Diermeier’s remarks in an interview with The Maroon last month, after he was appointed Isaacs’s successor. In response to a question about the University’s recent report on free expression and the interruption of a campus event, he said, “You’re going through the philosopher in me again.” When asked about the point at which he could step back from fundraising, he replied, “That’s a great question. That’s another philosophical question, right?” Wrong. To be sure, answers like “right” and “wrong” or “yes” and “no” are inimical to academics. But by that token, they are essential to administration. Clear, solid decisions are precisely what empower the obscure, fluid investigation for which the University exists. Or at least, I was emphatically taught as much in my Core classes. In particular, one instructor of mine was both an academic (“Senior Lecturer”) and an administrator (“Director”). Meanwhile, I was a first-year, slow to transition from the rigidity of high school assignments to the flexibility of college ones. Time and again, that instructor admonished me and my peers when we failed to distinguish between types of problems, not least “philosophical” and “pragmatic” ones. Repeatedly we were warned: confuse pragmatics for philosophy in a paper on, say, sexual assault, and risk not doing justice to the concept; do the reverse with a peer dealing with sexual assault and risk not doing justice to the survivor. Likewise, professors may study policy; Diermeier undoubtedly did at the Harris School. But at just as basic a level, provosts must make policy. When they don’t—when they pass off as conceptual the critical decisions about assault, pay, speech, and more that they are appointed as administrators to make—then we as a University find ourselves investigated by the U.S. Department of Education, struck by unions, interrupted by protests, and more. Worse, we find ourselves and our peers abused and ignored, underpaid and overworked, silenced and degraded—all of which is inimical to our scholarship at least. Naïvely, perhaps, in my time here, I have hardly advocated for the issues mentioned in this article, buying instead into the philosophy that students are here to focus on their studies. But given how our administration is jeopardizing our academic lives, that philosophy seems less and less pragmatic. And that seems wrong. |

Professionally...[my name] at yahoo dot com

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed